“Nature’s Clean-up Crew”

What do you think of when you hear the word “vulture”? Some people may think they are scary or gross. But vultures are unique and important creatures that play a critical role in the ecosystem: cleaning it up. Join us on this week’s virtual field trip to meet these magnificent animals!

WAYS TO LEARN ABOUT VULTURES

Attend the virtual field trip, Friday, February 5 at 10:30. Featuring live vultures!

Listen to a Navajo story that includes a brave deed by vulture.

Learn to identify vultures. We have suggestions for where to find them, and all you ever wanted to know about their life and behavior!

Clean up litter. What better way to learn from nature’s clean-up crew than to help clean up?

Virtual Field Trip: Friday, February 5 at 10:30am

Every Friday from 10:30 to 11-ish am, we hold a Zoom call live from the woods for anyone who wants to join. This week, we’ll have a special guest: a real, live turkey vulture and her caretaker!

If you haven’t registered for our field trips before, register here to get the link in your email:

When you register, your registration is good for every Friday.

Teachers: Your class can join these public field trips, or contact darcy@ruralaction.org to set up a zoom field trip just for your classroom.

Can’t make it, or can’t wait? Read on to learn about vulture’s special way of recycling and incredible flying abilities. Hopefully you’ll gain a new appreciation for the amazing turkey vultures!

Hello, my name is…

Like most plants and animals, Turkey Vulture go by many names:

- Scientists call them Cathartes aura, which is Latin for “cleansing breeze.”

- In North America, some say “buzzards” or “turkey buzzards.”

- In the Caribbean, people say “John crow” or “carrion crow.”

Today I will simply call them turkey vultures.

The common name Turkey Vulture was formed because some think the birds look like wild turkeys. Take a look back at our “Turkey Talk post”, and let us know if you agree.

Vultures in Stories

Listen to the Navajo story “Grandmother Spider Brings the Sun” in the video above. This is an old story of how darkness was turned to light and the animals that helped.

What is the buzzard character like in this story? Is the buzzard in this story different from how you’ve seen vultures in other stories or movies?

My favorite part of the story is when Buzzard tries to catch a piece of the sun in his large crown of feathers, but ends up burning off all his feathers leaving him bald with a bright red head!

How to identify a turkey vulture

“Turkey Vultures are large, dark birds with long, broad wings. Bigger than other raptors except eagles and condors, they have long ‘fingers’ at their wingtips and long tails that extend past their toe tips in flight. When soaring, Turkey Vultures hold their wings slightly raised, making a ‘V’ when seen head-on.”

–All About Birds

When you see turkey vulture from underneath, like in the picture above, the feathers on the tips and edges of its wings are white. This is a key clue that it is a turkey vulture, not another large bird.

Another key clue is the iconic red, bald head. Like the story Grandmother Spider Brings the Sun explains, turkey vultures have no feathers on their heads. This helps them to stay clean since they feed by thrusting their heads into the body cavities of rotting animals!

You might see another kind of vulture in our area: the black vulture. Like its name says, its bald head is black instead of red. Black cultures also have black feathers along the edge of their wings instead of white, with just a few white feathers at the tip.

Habitat

A large part of identifying animals is learning where they spend most of their time, so you know where to look for them.

Part of what animals look for in habitat is a place to have babies. Turkey vultures don’t make nests for their eggs like other birds. Instead, they find a dark crevice to lay their eggs. Sometimes, they use other birds’ abandoned nests to lay their eggs in. Turkey vulture eggs and hatchlings have been found in rock piles, caves, and hallowed out tree stumps.

The video above was taken at a former abandoned root cellar at Wisteria in Meigs County. In this video you can see a white and fluffy baby turkey vulture!

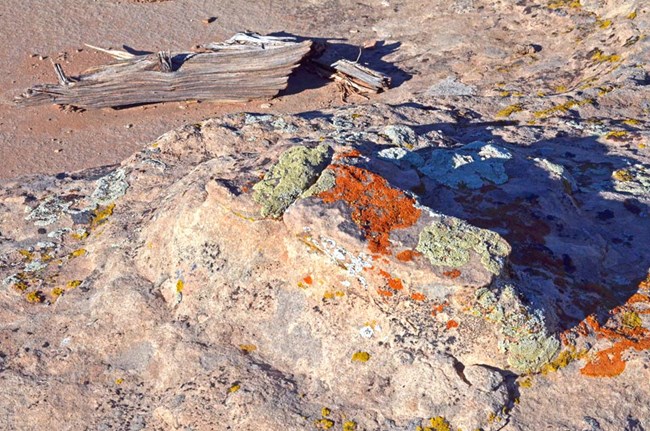

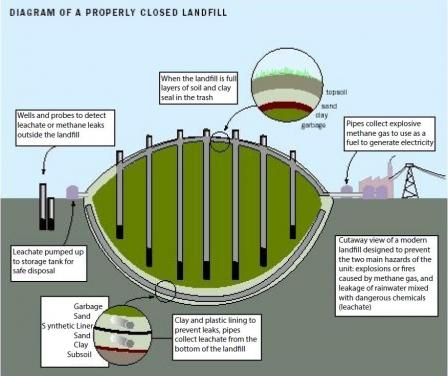

Adult and juvenile turkey vultures can be found on roadsides, suburbs, farm fields, countryside. They also gather near food sources like landfills, trash heaps, and construction sites. One of my favorite places in Athens is The Ridges, because I can always count on seeing turkey vultures or black vultures there.

Take A Vulture Hike

To see these marvelous birds soaring through the sky, try visiting these places people report seeing them often:

- Dairy Barn Lane near the Ridges in Athens

- Highland Park, and the nearby hillside above Grosvenor St, in Athens

- The hillside with the big white cross in Nelsonville (the cross is accessible by car or walking!)

- The “Athens” sign by the Richland Ave round-about.

Try checking out these locations, or tell us about a spot where you regularly see them!

One reason people see vultures in these spots might be that there is a nearby vulture roost, or group resting place. Groups of cultures often rest on big, dead trees. That’s because these trees have the height and space vultures need to take off in flight! With their 6-foot wing span, turkey vultures need a wide, clear peak to allow them to open up and catch a thermal current.

We’ll talk more below about thermal currents and how turkey vultures use them to soar through the sky.

One man’s trash is another man’s… dinner?

In the picture below, you can see an adult (red head) and a juvenile (dark gray head) turkey vulture scoping out a dumpster.

Remember how I said in some parts of the Caribbean

, people call them carrion crows? Well, that’s because carrion is what they eat! Carrion is a word used to describe the rotting flesh of dead animals.

Turkey vultures are scavengers. They cannot kill their own prey. Instead, they depend on their keen sense of smell to find animal carcasses. They actually have the largest olfactory (smelling) system of all birds. Its been reported that turkey cultures can smell carrion from over a mile away!

This excellent sense of smell not only helps them find their food. It also lets them know how long the animal has been dead

, and if it’s good to eat.Structures and their functions

The structure of an animal’s body parts can tell us a lot about the function, or what they use that body part for. Think about your body’s structure: its parts and how they work. What does it allow you to do that other animals can’t, or what are you limited by?

Feet

One way to tell that turkey vultures can’t kill their own prey is by taking a look at their feet. Let’s compare their feet to birds that do kill their own prey.

Red-tailed hawk feet. Photo: Frank Taylor

Turkey Vulture feet. Photo: David Orr

Try finding the differences and similarities in the feet of a red-tailed hawk (left) and a turkey vulture (right). What do you notice?

Keep in mind that ted-tailed hawks, like most raptors, kill their prey using the strength of their talons. Turkey vultures use their feet to help them rip flesh off carcasses.

Beaks

The beak of a bird can tell you a lot about what it eats!

Take a look at the pictures below of the hummingbird’s beak( left) and the turkey vulture’s beak(right). How are they the same or different?

Hummingbirds use their long, needle-like beaks to probe into a flower. This lets them to lap up nectar with their special tongues. Turkey vultures use their thick strong beaks to rip flesh off of dead animals.

Taking flight

Watch turkey vultures soaring in the air: they almost never flap their wings. This is because turkey vultures find thermal currents, or rising columns of warm air. They use their large wings to float on the warm air, lifting them high into the sky.

Though their wings are 6 feet across, the vultures only weigh 2-3 pounds. Floating this way, they can use very little energy while soaring through the sky. Aircraft pilots have reported seeing vultures as high as 20,000 feet and soaring for hours without ever flapping their wings!

Turkey vultures are not the only birds that catch these thermal currents. Other birds look for turkey vultures to help them find the rising columns of air. I often look for them above highways, where the warmth of cars creates thermals.

Humans have also looked to vultures to learn how to fly! Check out paraglider Bianca Heinrich and others competing in the world paragliding championships in the video below. Parasails catch thermal currents, letting people fly the same way as turkey vultures!

Migration

Many turkey vultures use southeast Ohio as their summer breeding territory. Then they fly south for the winter months. During their migration, they can fly over 200 miles a day!

In early spring and late fall, you can find large groups of turkey vultures preparing to leave or return. These large groups of turkey vultures are called kettles, because they look like water boiling in a kettle as lots of them make wobbly circles in the sky.

Recently, fewer and fewer turkey cultures bother to leave in the fall. Turkey vultures are slowly becoming year-round residents in Appalachia Ohio. Changing climate may explain why these birds no longer need to leave for the winter. With warmer winters, the long migration to South America is less necessary.

Celebrating turkey vultures

This video celebrates the time of year when turkey vultures would typically gather together before their long migration. The beginning talks about celebrating turkey vultures because they are unique and important creatures that are critical to the ecosystem.

One way we can help our ecosystem and honor turkey cultures is by helping them clean up waste! Turkey vultures help clean up the roadsides in their own special way by eating roadkill and other dead animals. You can help in a special human way by picking up litter outside. Take a bag with you on your next walk and help clean up!

How will you celebrate turkey vultures this week?