This week, we invite you to take a field trip (virtual or real) to a vernal pool. Read on to find out what they are!

I love vernal pools because they provide habitat for some of our most mysterious creatures in Ohio. Some people refer to them as “Appalachian tide pools” because they are ephemeral (don’t last very long) and harbor strange creatures like mole salamanders, fairy shrimp, diving beetles, and many others.

This time of year (late winter and early spring) is perhaps the best time to visit vernal pools. They are literally swimming with wildlife.

Vernal pools are low areas on the land that fill with water during the spring. They dry up by late summer. Because they dry up for part of the year, fish cannot live in vernal pools. This makes vernal pools ideal breeding habitat for amphibians (like frogs and mole salamanders) because there are no fish to eat their eggs.

These pools, depending on their size, also provide habitat for turtles, birds, and certain plants and trees. Dead leaves are the foundation of vernal pool food webs.

Resources for more information and inspiration about vernal pools:

- Watch this PBS video of three sisters exploring a vernal pool for inspiration!

- Ohio Department of Natural Resources has great information: Vernal Pools: Nature’s Nursery , including a downloadable field guide to amphibians.

- Ohio natural history expert Jim McCormac shares about salamanders and fairy shrimp with great photos.

- Ohio Environmental Council has information about vernal pools and their importance.

Assignment: Visit a Vernal Pool

First, find a vernal pool. This may be the most challenging assignment. Some great places to look are:

- The Cucumber Tree Trail that leads to Strouds Run State Park (parking at the end of Hope Drive, off E. State Street). Hike up the trail about ½ mile and there is an amazing vernal pool on the right (east) side of the trail.

- Lake Hope State Park has a great vernal pool that is on the north side of SR 278 and best accessed by turning on the road that leads up to the campground (Furnace Ridge Rd) and pulling off the right side of the road.

- The wetland visible from Little Fish Brewing Company and also accessible from the Hockhocking Adena Bikeway.

- There are numerous vernal pools along the Hockhocking Adena Bikeway, especially where the bike path is near the railroad.

- Anywhere you hear frog calls.

- Even puddles and big tire ruts can hold frog eggs and insects!

American toads are much more flexible in their “definition” of vernal pools than, say, a spotted salamander. You can find American toads singing, breeding, and laying eggs in ponds that have fish, and also tire ruts that leave depressions big enough to hold water.

Here is a toad in a grassy tire rut! Photo by June and Kelly Cooke.

When you are at the pool:

- Before you get too close to the pool , listen for frogs, toads, or birds singing. Check out this site to study up on frog and toad songs. What do you hear?

- As you get closer, check any logs out in the water for turtles, who may be laying out if the sun is shining.

- Scoop up some water in a clear jar. Is the water clear or murky? is there anything swimming around? Repeat in a couple of different places.

- Sift through the leaves at the bottom of the pool. Can you find any leaves that look they have been eaten? What insects or other creatures could be eating these leaves?

- If you have a net, take a few sweeps with it and look carefully to see what you have found.

- Try to spot any frogs on the edge of the pool before they see you and jump in!

Things to try for different ages:

- Toddlers and parents

- Walk around the edge of the pond and watch your toddler be amazed at the frogs jumping away from your path.

- Measure the depth of the pool using a stick.

- Check the area for other wildlife your toddler knows about, such as tigers, elephants, giraffes, dragons, and deer.

- If you have an Athens County Public Library account, go to https://www.hoopladigital.com/ and search for the Frog and Toad series.

- Elementary and Middle

- Carefully roll over logs within 10-20 feet of the water to check for salamanders or other creatures. Make sure to roll the logs back in place but don’t squish any salamanders.

- High-school and beyond

- Measure the width and length of the vernal pool, and estimate its depth

- Take photos of all of the organisms you see and upload to iNaturalist.org, or use the iNaturalist app on your smartphone.

- See our one observation of a fairy shrimp within our bioblitz of Wayne National Forest’s Athens Unit.

- If you happen to have pH strips or water testing equipment, check out the acidity or alkalinity of the pools. The pH should be between 6-7 (near neutral).

To go even deeper…(but not into the water!):

- Make a prediction–what will this vernal pool be like in July? What about December?

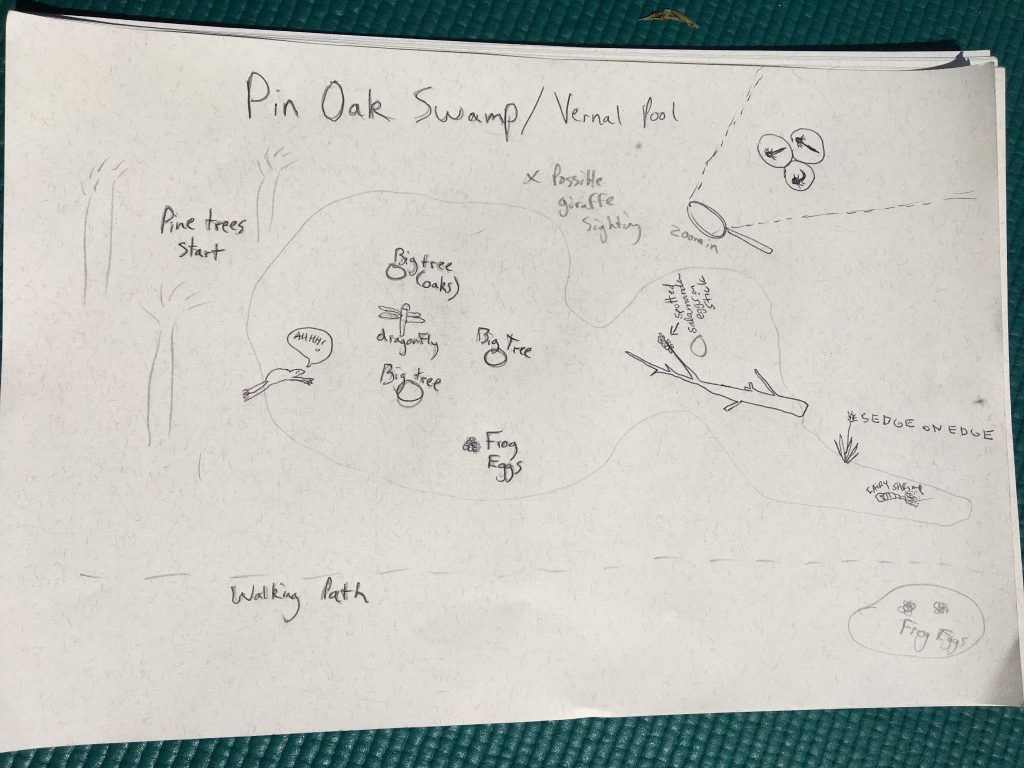

- Sketch the vernal pool and include what you think are the noticeable parts of the vernal pool, like a big tree or a fallen log that turtles like, or a mound of dirt next to a hole made by a digging crawdad.

What if I can’t get to a vernal pool?

No problem. Try these activities!

- Check any puddles in or around your yard for life, such as mosquito larvae or butterflies visiting the puddles. Any source of water might attract wildlife!

- Make a toad abode to provide habitat for toads when they leave the vernal pools.

- Explore the links at the beginning of the post. Draw the plants, animals, and other features you think you would find at a vernal pool, based on your research.

7 replies on “Vernal Pools, Part I”

Hi Joe, we have a couple of vernal pools on our property and some of them have eggs and some don’t. My dad said that it was because they hadn’t been there long and there were no frogs born there and frogs go to the same pool they were born in I wonder how they newer pools get frogs when no frogs go there so none were born there how do frogs get there

Hey Quinn, and thank you for the great question! Your dad is mostly right–a lot of frogs do return to the same pools in which they were born. In the case of wood frogs, some of the frogs who hatch from that pool will migrate to other pools to breed the following year. This behavior of wood frogs may be one reason why they have been able to inhabit a huge portion of North America, all the way up to the Arctic Circle. I have been thinking about this same question because a few weeks ago I saw wood frog eggs in a brand new pool that was just made by someone working on a trail over the winter. I always wonder how the frogs find the right spots–they must have amazing senses for it! Thanks so much for the comment and keep observing!

We saw a few tadpoles in the cucumber lake. It is hard to see because of the reflection. Can you spot it?

Yes, I see it! If the tadpoles have feathery gills around their neck, you’re looking at a salamander tadpole (most likely spotted salamander or jefferson salamander). No external gills means it’s a frog or toad. Thanks so much for sharing what you saw!

Joe

[…] you get enough of vernal pools last week? No? Me neither! Vernal pools are amazing and teeming with life. Check out Joe’s […]

Today I found a young northern water snake in a shallow vernal pool, presumably eating tadpoles. This is the first time I’ve ever seen this snake species in a vernal pool habitat.

[…] March, we wrote about vernal pools and what lives in them. But why are these pools so important for the frogs and salamanders in our […]