If I had to choose a favorite day of the week, it would be Sunday. I roll out of bed in my homemade pajamas with breakfast on my mind. I have more time to make breakfast, so I make French toast, waffles, or blueberry pancakes. It’s hard to pick my favorite. But the same thing always goes on top: maple syrup.

Sticky and sweet, maple syrup adds a soft golden flavor to any food. You can buy it in glass bottles or plastic jugs to deck out your Sunday breakfasts. But before it reaches the store, maple syrup starts in forests like ours in southeast Ohio. Maple syrup and honey are the only local ways to sweeten your food!

On this week’s virtual field trip, educator Joe will show us how to get the sweet liquid goodness out of maple trees and into your belly.

Here are some options for getting to know nature’s sweetener:

Attend the virtual field trip, Friday, March 5th at 10:30 am on Zoom.

On your own , inside: Read an indigenous story about the origins of maple syrup.

On your own , outside: Practice identifying sugar maple trees and watch for sap.

Virtual Field Trip, March 5th at 10:30 am

Every Friday from 10:30 to 11:15 AM, we hold a Zoom call live from the woods for anyone who wants to join. This week, Joe will show us how he makes syrup and how to identify maple trees.

If you haven’t registered for our field trips before, register here to get the link in your email:

When you register, your registration is good for every Friday.

Teachers: Your class can join these public field trips, or contact us to set up a zoom field trip just for your classroom.

What is maple sap?

A maple is a kind of tree. Syrup is made from the sap that flows in a maple tree.

Sap is a liquid that moves up and down inside a tree, just behind the bark. Sap moves water and nutrients to parts of the tree that need it. It makes trees strong and healthy. If you’ve ever seen sticky, clear globs on the outside of tree bark, you were likely looking at that tree’s sap.

When leaves photosynthesize

, they turn sunlight into sugar. That sugar is in the sap. The tree uses the sugar for energy–unless we tap it for our own energy!All maple trees have sap inside them. The best sap for making maple syrup, though, comes from sugar maple trees. The name doesn’t lie: a sugar maple has more sugar in its sap than any other species of maple tree.

Sugar Maples

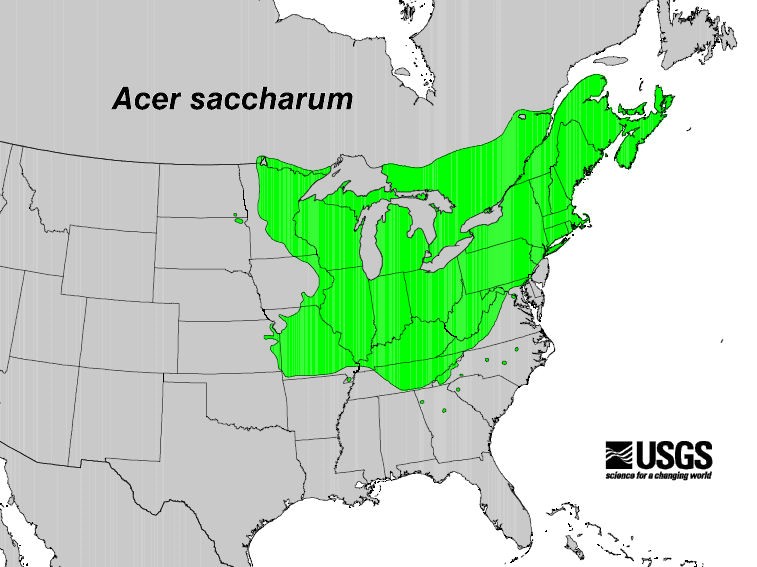

Good news for us: sugar maple trees call southeastern Ohio home. Sugar maples lose their leaves year after year, making them a deciduous tree. Most trees in southeast Ohio forests are deciduous, so sugar maples fit in.

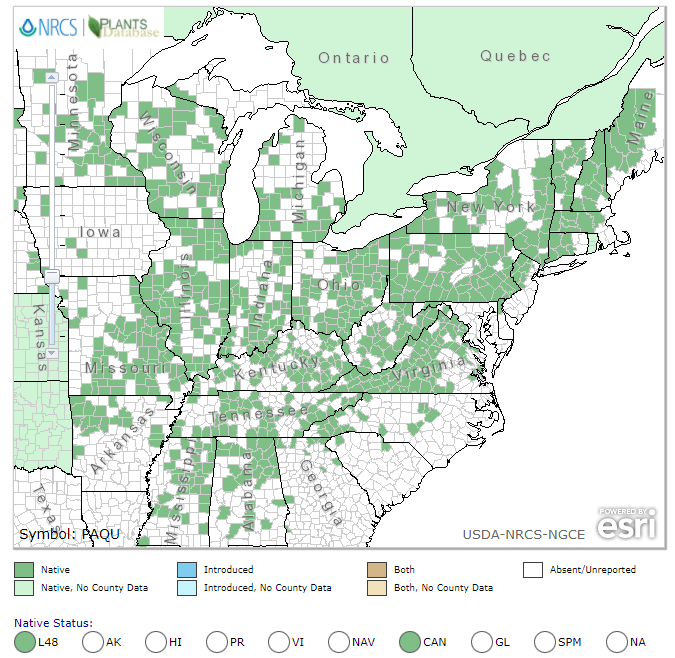

Many other states in the eastern United States are lucky to have sugar maples, too. The green parts of this map show places with the right climate and habitat for sugar maples to grow. Notice that the green extends into Canada, too.

Your turn: Find Sugar Maples

Take a walk to see if you can find any sugar maples! They are common even in parks and neighborhoods. Joe likes to find them in the spring and summer, so he’s ready to tap them when February comes.

Sugar maples often grow on the middle or low part of hills, or near old farms (where people planted them). They do better in backyards than near the street, where cars and salt bother them.

Here are some ways to recognize a sugar maple:

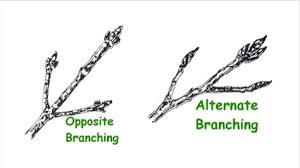

- Look for opposite branching. The twigs on any maple always grow directly across from each other. The leaves do this too. Only a few trees in Ohio do this.

- Look at the buds on the end of the twig. There’s one long bud in the middle, and two short ones on either side. You can identify a maple even when there are no leaves with this trick!

Sugar maple buds are brown (like the picture above). If the buds are red, you have a red maple instead (like the picture below)

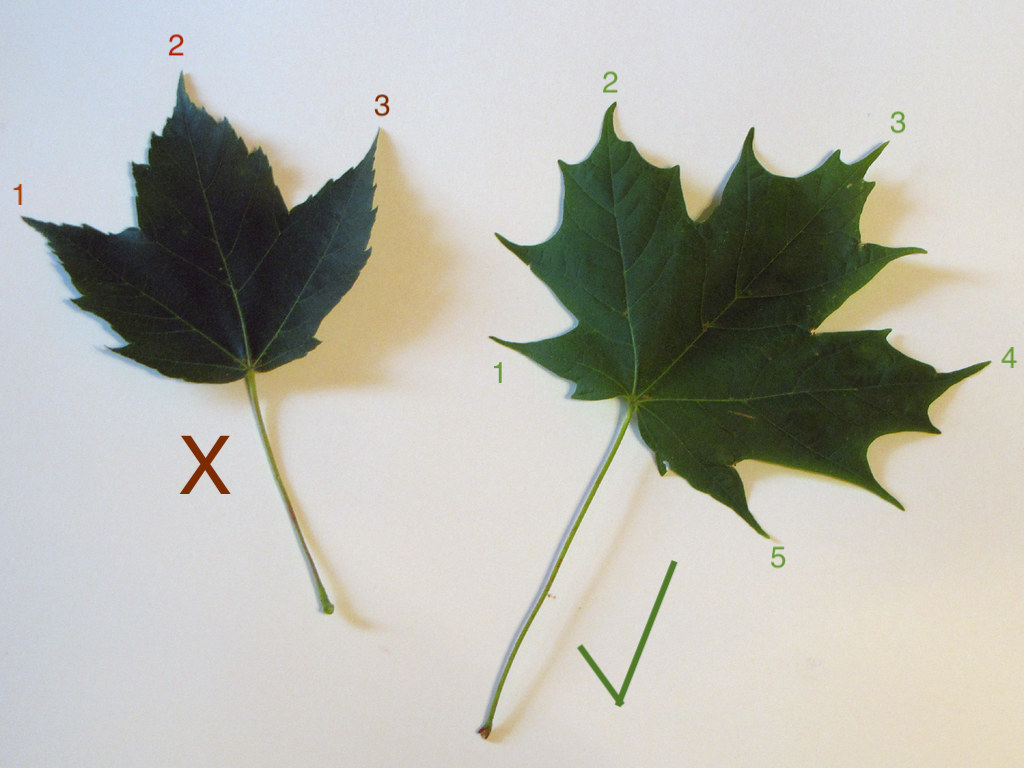

- The leaf looks like the flag of Canada. A sugar maple leaf has 5 lobes (or sections). Red maples have only 3. Another way to think about it is that sugar maple leaves are pointed , not round at the bottom. What differences do you see between the red and sugar maple leaves in this picture?

Maybe picturing the Canadian flag will help you remember!

From sap to syrup

Maple syrup can’t be made year round. Sap only starts flowing when the weather is just right. The best time for tapping trees for sap is right now! Cold nights below freezing and warmer days create a freeze/thaw cycle that pushes the sap through the tree. But how do you get to the sap?

Watch this video from the Ohio Department of Natural Resources to see how to “tap” a sugar maple tree to collect the sap.

Sap isn’t the same thing as syrup, though. Buckets of sap have to be boiled for a long time. Boiling evaporates the water and leaves behind the sugar. It takes 30-40 gallons of sugar maple sap to make 1 gallon of syrup!

Below is a photo of Joe’s sap boiling station. He has a thermometer to measure the temperature of the sap.

Voila! Boiled sugar maple sap makes maple syrup.

Who first made maple syrup?

It certainly wasn’t Joe! Indigenous folks have been making maple syrup to flavor their food long before Europeans colonized this land. The first Europeans to make maple syrup in the 1500s learned from the Native Americans.

Here are some early ways Indigenous people used to make maple syrup:

- Repeatedly freezing the sap and getting rid of the ice. The water in the sap will freeze, but the sugar won’t!

- Boiling the sap on hot rocks to evaporate the water out.

The Anishinaabe have a story about why it takes so much sap to make just a little syrup! Listen to an educator at Cumming Nature Center tell it:

Other Indigenous groups in the Great Lakes region

, like the Chippewa and Ojibwe, have similar sap stories. If you are interested in reading more Indigenous lore about maple syrup , this page has two other short stories to share.The maple syrup economy

Humans have long depended upon the natural world for food and trade. Maple syrup is no exception. Not only do we use maple syrup as a sweetener on our pancakes and in our teas, many people make their living from processing sap into maple syrup.

Twelve states in the US produce maple syrup to sell. In Ohio, 900 people boil sap into maple sugar to sell in stores and at farmers’ markets. Those 900 producers make 100,000 gallons of maple syrup each year. Maple syrup contributes $5 million to Ohio’s economy each year. Sugar maple trees provide us with a natural sweetener, but it also provides many folks with an income to house and feed their families. Where would we be without sugar maple trees?

Next time you jump out of bed for a Sunday breakfast, thank sugar maple trees and Indigenous people who inhabited this land before us for maple syrup. And maybe after this week’s Virtual Field Trip, you can make your own like Joe.