A frozen lake, pond, or wetland might be a tempting ice-skating rink. But a thick layer of ice on top doesn’t stop aquatic life from calling these places home. This week, we explore how animals survive when their home freezes into ice. You can:

Attend the virtual field trip, Friday, February 19th at 10:30 am on Zoom.

Find a winter nature spot to make observations. The more you visit, the more you’ll notice!

Read about beavers and wetlands in the rest of the post, then draw a beaver’s world.

Virtual Field Trip, Feb. 12 at 10:30 am

Every Friday from 10:30 to 11-ish am, we hold a Zoom call live from the woods for anyone who wants to join. This week, we’ll be investigating frozen ponds and those who live in them.

If you haven’t registered for our field trips before, register here to get the link in your email:

When you register, your registration is good for every Friday.

Teachers: Your class can join these public field trips, or contact us to set up a zoom field trip just for your classroom.

The birth of a wetland

By Emily

Last week, Sarah and I visited the Rutherford Wetland at the Ora Anderson Nature Trail outside Carbon Hill. I have visited countless wetlands in my life, both near my home in Athens County and far. I am always struck by how beautiful and calm these places can be. I love to see waterfowl like ducks and blue herons. But, this wetland is especially interesting to me.

The Rutherford Wetland hasn’t always been water. It used to be woods along Monday Creek, and sometimes the woods flooded. Then, all the trees were cut down to make farms. And a railroad was built right through these low-lying farm fields.

In the 1990s, the Wayne National Forest took over the land, and it began to change again. Beavers moved in. The beavers dammed up the farm fields, flooding them. That created the diverse wetland I saw last week.

Beaver Dams

Beavers create or change wetlands with their dams. The dams are walls of sticks and mud. These walls block streams from flowing freely. The water usually gets deeper and spreads out into a pond or wetland. Plants change, and animals are drawn to the habitat. This is how a bunch of fields turned into the Rutherford wetland!

I find the Rutherford Wetland so interesting because its story shows how wetlands can adjust to new conditions. This land was stripped of all its trees, heavily farmed, and had an industrial railroad running through it. But now it’s a healthy ecosystem for beavers, fish, ducks, and songbirds.

Wetlands get to work

All wetlands have ways to deal with flooding and pollution. Wetlands soak up extra water that human concrete keeps from soaking into the soil. They absorb lots of rainwater, too.

Wetlands hold onto that water and release it more slowly. This prevents floods when it’s too rainy. And when the weather is too dry, wetlands keep streams flowing with all the water they saved up.

The quality of our water is improved when it goes through a wetland. Wetlands filter out pollutants from our lawns

, cars and factories. This makes our drinking water safer and better for animals to live in. This isn’t an excuse to dump our waste in wetlands, but they do a good job cleaning up what mess we do make.A wetland comeback story

Madison shared with me a great story about a wetland in New Jersey that was mistreated. But like the Rutherford wetland, it bounced back with human help. Now it provides habitat to fish, crabs, and seabirds. Listen to me read it, if you’d like:

Wetlands, and the critters inside them, also adapt to winter. When Sarah and I were at Rutherford last week, the whole wetland was frozen. The best way to start understanding these changes? Make your own observations!

Outdoor activity: Watching the seasons change

You will need:

- Paper or a notebook

- Something to write or draw with

Now is a great time to observe winter changes—Athens County is currently in a level 2 snow emergency. This is some pretty beautiful winter weather, but it’s also recommended you don’t drive. So pick an outdoor area near your home to make your winter observations.

Your nature spot doesn’t have to be big. A pond, little stream, or small garden is nice. But even a patch of grass or bushes is fine.

At your spot, observe nature and take detailed notes or drawings. Do it over and over and over and over and over again! Why? If you watch day after day, you’ll be an eyewitness to the wonders of the changing seasons. Winter into spring is a magical time when little details change each day. Some things you can only see at this time of year.

You might write or draw:

- What you see

- What you hear

- What the weather feels like

- What stands out to you about the area

- How has snow , ice or cold changed the area?

- What are plants and animals doing during this cold time? Do you see any evidence of them?

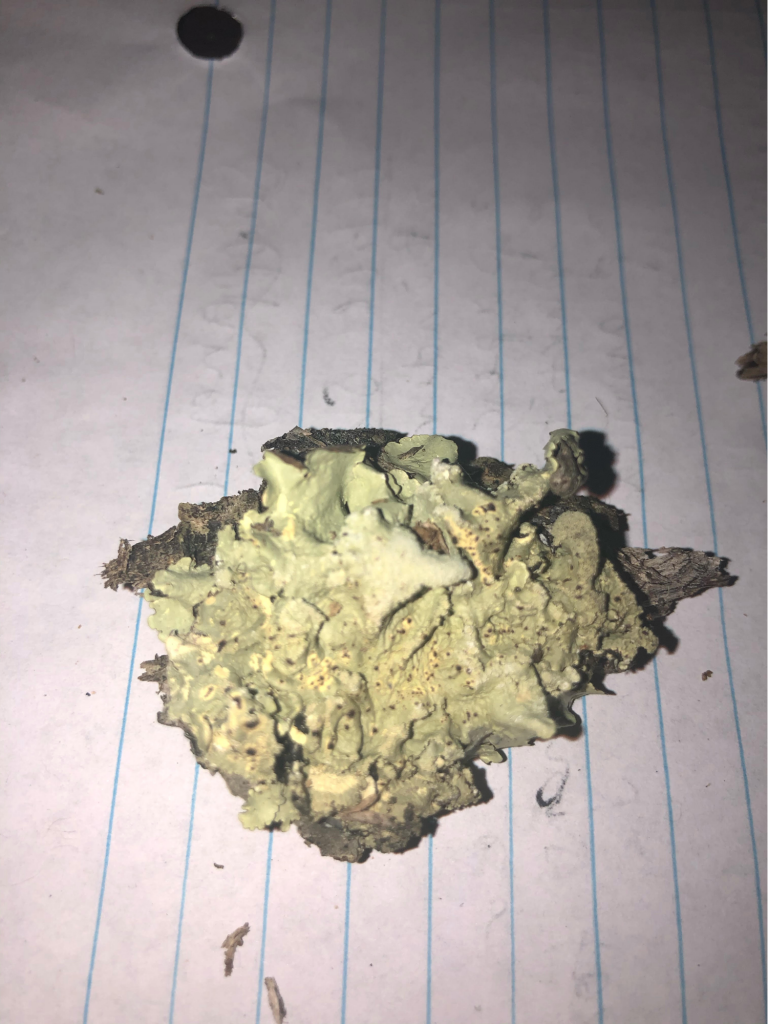

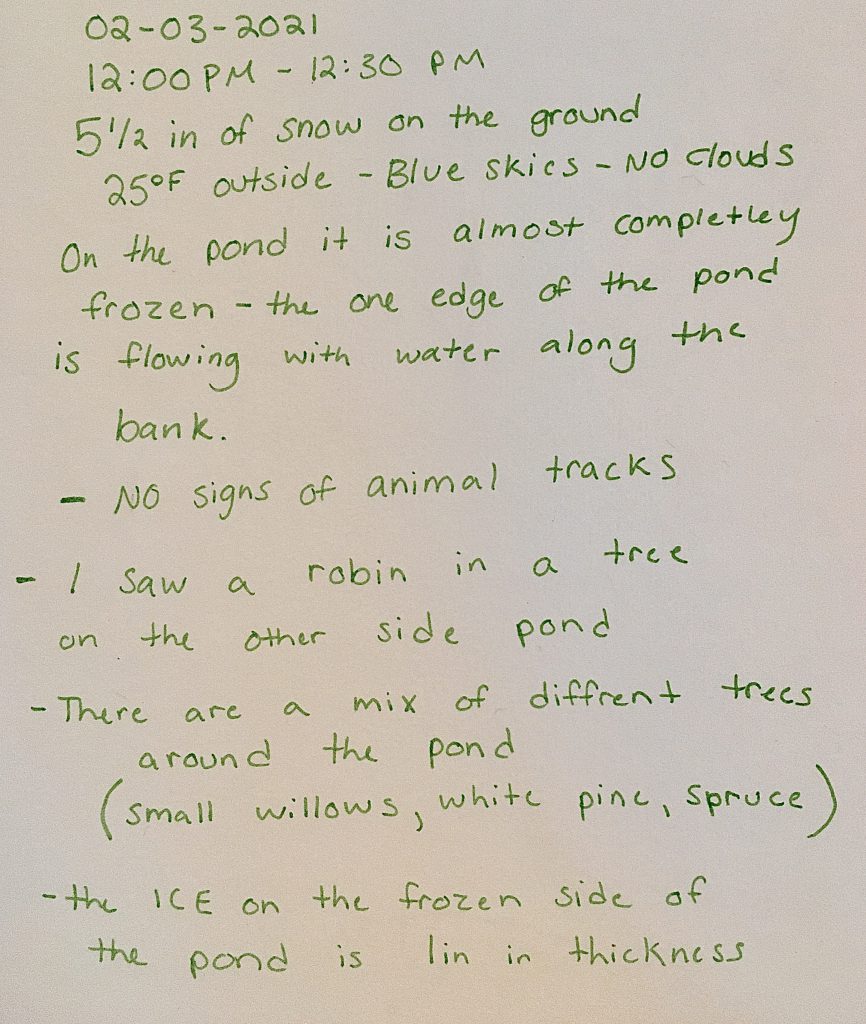

Here is an example from my time by a pond:

It’s okay if you can’t identify all the plants or animals you see. Describe them the best you. If you want to, you can look for them in field guides later.

Now that we know more about wetlands, let’s look at the animals who live in them in winter.

Animal adaptations: Tools for Survival!

By Sarah

How do humans adapt to winter? You may think of putting on coats, mittens and hats to stay warm.

Now imagine that you live in a frozen wetland. How could you keep yourself warm while being wet? This might be difficult for us people, but animals have many adaptations to handle it.

What are adaptations? Think of adaptations as tools that animals are born with that help them survive in their environment. Living in the wild is a rough life. You are exposed to wind, storms, and heat. So animals have adaptations to help them live in harsh weather conditions. The wild also has predators and no grocery stores, so animals also have adaptations to help them hide, fight, and get food.

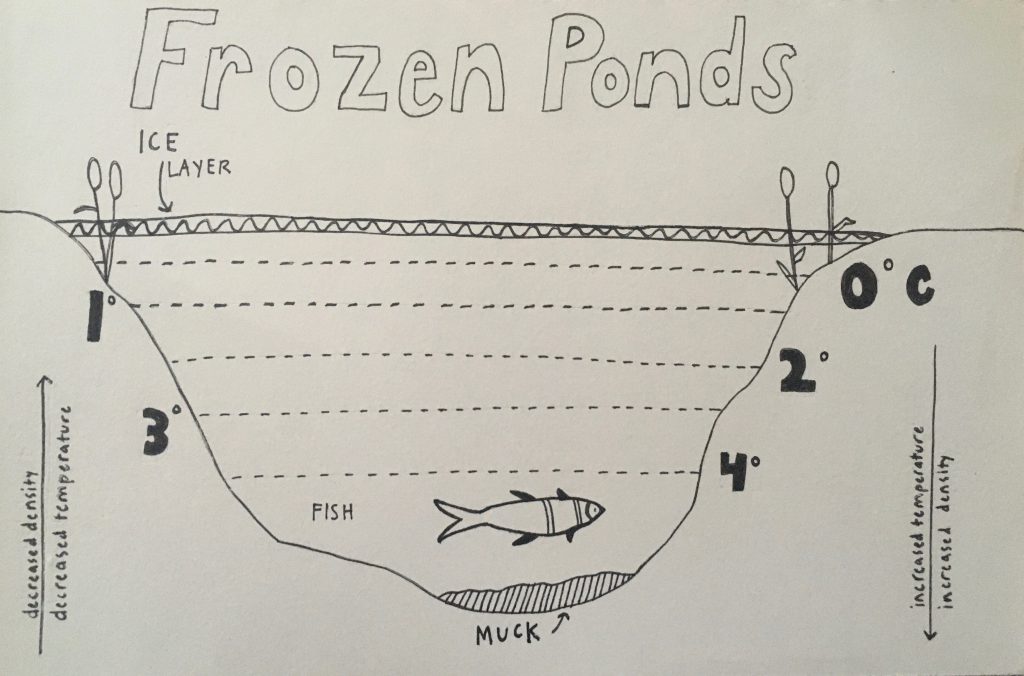

How might an animal adapt to a pond freezing? The water is chilly

, there’s less food, and ice keeps you from the surface. Yet the layer of ice on top actually helps keep the water below warmer.- Fish survive the winter by hanging out near the bottom of the lake, where the warmest water is. They enter a winter rest state , when their heartbeat slows down. They need less food and oxygen.

- Turtles burrow into the mud at the bottom of the pond, where it’s even warmer. Like fish, their bodies slow down, and they switch to breathing out their butt!

- Wood frogs leave the pond, and bury themselves in the ground in the woods nearby. They have a special chemical in their body that lets them freeze solid, like a popsicle! They thaw out in sprin and hop off.

Let’s look more closely at how one species in particular is adapted to life in the winter wetland. It’s the species that built the Rutherford Wetland: the beaver.

How Beavers Have Adapted

The arrows point at unique features the beaver has to live in wetlands! Such wild wetland areas are vast and you need to be able to swim well throughout the water. How does the beaver do this? How do you make a house on the water? You need to have some good tools to start. All these adaptations the beaver needs to live in a wetland!

The green arrow: two big teeth for chewing wood. The two square teeth at the front of beavers’ mouths are called incisors. This adaption is a tool for cutting! Remember this by thinking…

“I use scissors to cut paper and beavers use incisors to cut trees down!”

Beavers need these incisor teeth to cut down trees. They use these to build lodges

, their homes. The beavers need lodges to stay warm during the winter. Lodges also are a safe place to be, because their entrance is underwater. There aren’t many other animals who can swim underwater, then crawl up into a dry lodge.Beavers also use the incisors to gnaw on the outer layer of sticks. Beavers eat the just the bark of sticks and vegetation in the water. They don’t eat the full-sized trees they bite down. Before winter, they store lots of these sticks in the water. The cold water acts like a refrigerator, keeping their food fresh all winter.

The red arrow: feet for swimming. Beavers feet remind me of a scuba diver’s flippers. While a beaver is quite slow on land, they move quickly through the water. Did you know beavers can hold their breath and swim underwater for up to fifteen minutes? That’s pretty impressive!

The blue arrow: a wide tail. A beaver’s tail has many uses! Like their feet, their tail makes them good swimmers. Beavers also use their tails for communicating. If they think a predator is nearby, they will slap their tail against the water. The slap warns each other of danger, and hopefully scares off any predator, before they dive into the water.

Beavers wouldn’t survive winter if it wasn’t for their tails. In the summer, beavers stock up on snacks to build extra fat to keep them warm and well fed in the scarce, winter months. This fat is stored in their tails. When winter rolls around, the fat will trickle out of their tails into the rest of their body. Beaver’s tails are almost like their pantry and coat closet in one, stocking up on food and warmth.

Of course, fur also keeps beavers cozy, even when there’s ice on the pond. Beavers have two layers of fur. The inner layer keeps their body heat in and the cold out, like a parka. The outer layer of fur makes water roll off, like a raincoat. The drier you are, the warmer you are.

Indoor activity: Design like a beaver!

Beavers build lodges similarly to how pioneers built log homes: by cutting down the trees around them. Pioneers used axes to cut down a tree. The beaver use their own tool, their large incisor teeth, to cut down the tree. Beaver lodges are also made with grasses, mosses and mud!

Beaver lodges come in all shapes and sizes. Some of the key elements of the beaver lodge include…

- An entry point (You can see how beavers enter and leave their lodge in this picture )

- A place to store food, sticks and twigs, for the winter

- A dry spot to sleep

Get a piece of paper and start drawing! Imagine you are a beaver living in a wetland: what does your lodge look like? Where is the dam? Do you live with a family of beavers? Where do you keep your beaver snacks? What other animals and plants live there?

We’d love to see your drawings in the comments or at the virtual field trip this week!